Remembering Moby Doll - The first ever orca in captivity

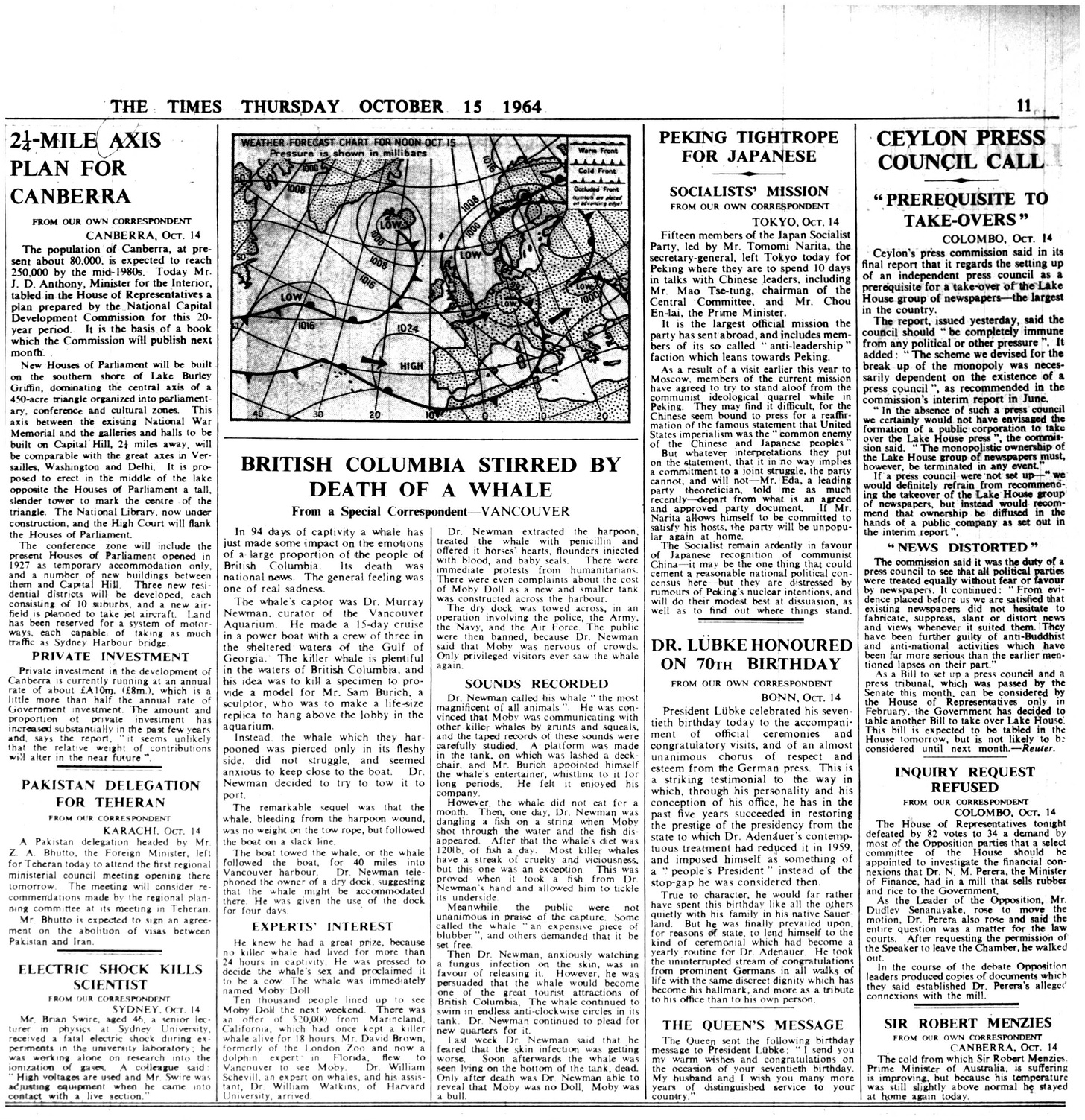

Oct. 9, 1964, the killer whale who changed the world died in a makeshift tank in Vancouver, BC. Here's the story of "the most bizarre moving day Vancouver has ever seen."

October 9, 1964 - Moby Doll, the first orca displayed in captivity, drowned in a makeshift tank (built by the Canadian military) at Jericho Beach in Vancouver. He was about four-years-old. From the time I first heard his story - from Sea Shepherd founder, Paul Watson - Moby Doll obsessed me on pretty much the same level Moby Dick obsessed Ahab. I actually chased Moby Doll for decades longer than Ahab chased Moby Dick and shared the story of Moby’s life and legacy - and humanity’s bizarre and brutal history with killer whales - in my book, The Killer Whale Who Changed the World - which sparked the Skaana podcast. To check out the audiobook for free, Spotify now gives every listener 15 free audiobook hours a month - so this is your chance to listen to me reading/sharing Moby’s epic story. And the book is still available through bookstores everywhere.

Here’s an excerpt from The Killer Whale Who Changed the World - the story of how Moby made it from his temporary home in a Vancouver dry-dock into a make-shift sea-pen off Jericho Beach while the world watched. This is from the chapter Million Dollar Baby.

The pen traveled the seven miles across the water at between three and four knots. Perhaps because it was a military operation, the trip began with military precision, and the fleet of a half dozen tugs was accompanied by a naval vessel. Meanwhile, navy divers raced to finish their cage before the convoy arrived. Whale watchers crowded the shoreline, approached by boat, and someone even flew over the dry dock in a floatplane to witness the epic journey.

It was all smooth sailing, until a ferry sent ripples through the water. The Sun reported that ten-foot-high waves “rocked the dry-dock and caused Moby Doll to squeal in panic as the water heaved violently. Three of the five lines holding an accompanying powered scow snapped.” Fortunately, Wallace had sent fifteen men to supervise the move. The workers quickly reconnected the lines. In about ten minutes, the waves, whale, and moving men had calmed down.

Once the dry dock arrived at the naval base, the moving team had to wait four hours for the water to rise so that they could take advantage of the 4:20 flood tide. This extra time allowed navy divers to take one last tour of the pen to confirm that it wasn’t just closed off from outside waters but also clear of debris and sharp edges. The Life photographer and a CBC cameraman tried to take underwater photos of the whale inside the dry dock, but the water wasn’t clear enough.

When the foreman felt the tide and time were right for the transfer, he signaled the tugs and ordered his crew to hook up the chute. Once everything was set and the tide lifted the rear of the dry dock, the perfect plan fell apart. Fred Allgood from the Sun referred to what happened next as “Moby’s finest hour.”

The Colonist described it as “a stubborn cat-and-mouse battle with her captors.”

The Toronto Star called it “the most bizarre moving day Vancouver has ever seen.”

The whale had arrived at her new home, but she wasn’t moving. “Moby lost her self-control and gave a display of feminine temper,” wrote Allgood. “She squirmed in the water, thrashed angrily, twisted in many directions and howled into the hydrophone Dr. McGeer had concealed in the dock.”

The dry dock was lowered by a pump, the back end was raised, and Moby was expected to float down the chute and into her new home. Burich and Penfold hopped into a small boat to guide their whale, but she wasn’t interested. “She refused to cooperate, backed, turned, attacked the boat and fought for her freedom. For 20 minutes she glared angrily at the crowd around the pen and flicked her tail defiantly,” wrote Allgood.

The Province reported that “the captured killer whale bucked, twisted, squealed angrily, thrashed the water and charged the boat that tried to nudge her into her new home.”

That was when Penfold probably became the first human in history to intentionally hit a whale. After two hours of trying to cajole, dump, and scare the captive into her new home, the no-nonsense former prison guard grabbed the whale’s dorsal fin and shoved it in an attempt to shock her into moving. The crowd of scientists, frogmen, army engineers, dockworkers, and media cheered. Moby Doll was unfazed. She didn’t snap at Penfold, but she didn’t change direction either.

Allgood wrote, “With a heave and a twist she refloated herself. The fire had gone out of her and she slipped into the pen defeated. Engineers quickly lowered the gate in position. Moby Doll was home. No mighty bull killer whales greeted her distress signals, and so she surrendered suddenly, and reluctantly drifted into her new pen at Jericho. She sensed she was trapped. Instead of charging the army engineers as they bolted the gate of her new pen in position, she meekly circled her new home.”

And for something completely different… here’s the latest post from my personal substack… a look at one of the all-time great Vancouver Canucks.